In our first blog post, we covered some secure design principles and how they guided the architecture of gVisor as a whole. In this post, we will cover how these principles guided the networking architecture of gVisor, and the tradeoffs involved. In particular, we will cover how these principles culminated in two networking modes, how they work, and the properties of each.

gVisor’s security architecture in the context of networking

Linux networking is complicated. The TCP protocol is over 40 years old, and has been repeatedly extended over the years to keep up with the rapid pace of network infrastructure improvements, all while maintaining compatibility. On top of that, Linux networking has a fairly large API surface. Linux supports over 150 options for the most common socket types alone. In fact, the net subsystem is one of the largest and fastest growing in Linux at approximately 1.1 million lines of code. For comparison, that is several times the size of the entire gVisor codebase.

At the same time, networking is increasingly important. The cloud era is arguably about making everything a network service, and in order to make that work, the interconnect performance is critical. Adding networking support to gVisor was difficult, not just due to the inherent complexity, but also because it has the potential to significantly weaken gVisor’s security model.

As outlined in the previous blog post, gVisor’s secure design principles are:

- Defense in Depth: each component of the software stack trusts each other component as little as possible.

- Least Privilege: each software component has only the permissions it needs to function, and no more.

- Attack Surface Reduction: limit the surface area of the host exposed to the sandbox.

- Secure by Default: the default choice for a user should be safe.

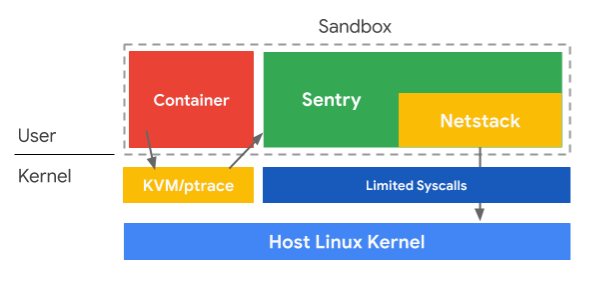

gVisor manifests these principles as a multi-layered system. An application running in the sandbox interacts with the Sentry, a userspace kernel, which mediates all interactions with the Host OS and beyond. The Sentry is written in pure Go with minimal unsafe code, making it less vulnerable to buffer overflows and related memory bugs that can lead to a variety of compromises including code injection. It emulates Linux using only a minimal and audited set of Host OS syscalls that limit the Host OS’s attack surface exposed to the Sentry itself. The syscall restrictions are enforced by running the Sentry with seccomp filters, which enforce that the Sentry can only use the expected set of syscalls. The Sentry runs as an unprivileged user and in namespaces, which, along with the seccomp filters, ensure that the Sentry is run with the Least Privilege required.

gVisor’s multi-layered design provides Defense in Depth. The Sentry, which does not trust the application because it may attack the Sentry and try to bypass it, is the first layer. The sandbox that the Sentry runs in is the second layer. If the Sentry were compromised, the attacker would still be in a highly restrictive sandbox which they must also break out of in order to compromise the Host OS.

To enable networking functionality while preserving gVisor’s security properties, we implemented a userspace network stack in the Sentry, which we creatively named Netstack. Netstack is also written in Go, not only to avoid unsafe code in the network stack itself, but also to avoid a complicated and unsafe Foreign Function Interface. Having its own integrated network stack allows the Sentry to implement networking operations using up to three Host OS syscalls to read and write packets. These syscalls allow a very minimal set of operations which are already allowed (either through the same or a similar syscall). Moreover, because packets typically come from off-host (e.g. the internet), the Host OS’s packet processing code has received a lot of scrutiny, hopefully resulting in a high degree of hardening.

Writing a network stack

Netstack was written from scratch specifically for gVisor. Because Netstack was designed and implemented to be modular, flexible and self-contained, there are now several more projects using Netstack in creative and exciting ways. As we discussed, a custom network stack has enabled a variety of security-related goals which would not have been possible any other way. This came at a cost though. Network stacks are complex and writing a new one comes with many challenges, mostly related to application compatibility and performance.

Compatibility issues typically come in two forms: missing features, and features with behavior that differs from Linux (usually due to bugs). Both of these are inevitable in an implementation of a complex system spanning many quickly evolving and ambiguous standards. However, we have invested heavily in this area, and the vast majority of applications have no issues using Netstack. For example, we now support setting 34 different socket options versus only 7 in our initial git commit. We are continuing to make good progress in this area.

Performance issues typically come from TCP behavior and packet processing speed. To improve our TCP behavior, we are working on implementing the full set of TCP RFCs. There are many RFCs which are significant to performance (e.g. RACK and BBR) that we have yet to implement. This mostly affects TCP performance with non-ideal network conditions (e.g. cross continent connections). Faster packet processing mostly improves TCP performance when network conditions are very good (e.g. within a datacenter). Our primary strategy here is to reduce interactions with the Go runtime, specifically the garbage collector (GC) and scheduler. We are currently optimizing buffer management to reduce the amount of garbage, which will lower the GC cost. To reduce scheduler interactions, we are re-architecting the TCP implementation to use fewer goroutines. Performance today is good enough for most applications and we are making steady improvements. For example, since May of 2019, we have improved the Netstack runsc iperf3 download benchmark score by roughly 15% and upload score by around 10,000X. Current numbers are about 17 Gbps download and about 8 Gbps upload versus about 42 Gbps and 43 Gbps for native (Linux) respectively.

An alternative

We also offer an alternative network mode: passthrough. This name can be misleading as syscalls are never passed through from the app to the Host OS. Instead, the passthrough mode implements networking in gVisor using the Host OS’s network stack. (This mode is called hostinet in the codebase.) Passthrough mode can improve performance for some use cases as the Host OS’s network stack has had an enormous number of person-years poured into making it highly performant. However, there is a rather large downside to using passthrough mode: it weakens gVisor’s security model by increasing the Host OS’s Attack Surface. This is because using the Host OS’s network stack requires the Sentry to use the Host OS’s Berkeley socket interface. The Berkeley socket interface is a much larger API surface than the packet interface that our network stack uses. When passthrough mode is in use, the Sentry is allowed to use 15 additional syscalls. Further, this set of syscalls includes some that allow the Sentry to create file descriptors, something that we don’t normally allow as it opens up classes of file-based attacks.

There are some networking features that we can’t implement on top of syscalls that we feel are safe (most notably those behind ioctl) and therefore are not supported. Because of this, we actually support fewer networking features in passthrough mode than we do in Netstack, reducing application compatibility. That’s right: using our networking stack provides better overall application compatibility than using our passthrough mode.

That said, gVisor with passthrough networking still provides a high level of isolation. Applications cannot specify host syscall arguments directly, and the sentry’s seccomp policy restricts its syscall use significantly more than a general purpose seccomp policy.

Secure by Default

The goal of the Secure by Default principle is to make it easy to securely sandbox containers. Of course, disabling network access entirely is the most secure option, but that is not practical for most applications. To make gVisor Secure by Default, we have made Netstack the default networking mode in gVisor as we believe that it provides significantly better isolation. For this reason we strongly caution users from changing the default unless Netstack flat out won’t work for them. The passthrough mode option is still provided, but we want users to make an informed decision when selecting it.

Another way in which gVisor makes it easy to securely sandbox containers is by allowing applications to run unmodified, with no special configuration needed. In order to do this, gVisor needs to support all of the features and syscalls that applications use. Neither seccomp nor gVisor’s passthrough mode can do this as applications commonly use syscalls which are too dangerous to be included in a secure policy. Even if this dream isn’t fully realized today, gVisor’s architecture with Netstack makes this possible.

Give Netstack a Try

If you haven’t already, try running a workload in gVisor with Netstack. You can find instructions on how to get started in our Quick Start. We want to hear about both your successes and any issues you encounter. We welcome your contributions, whether that be verbal feedback or code contributions, via our Gitter channel, email list, issue tracker, and Github repository. Feel free to express interest in an open issue, or reach out if you aren’t sure where to start.